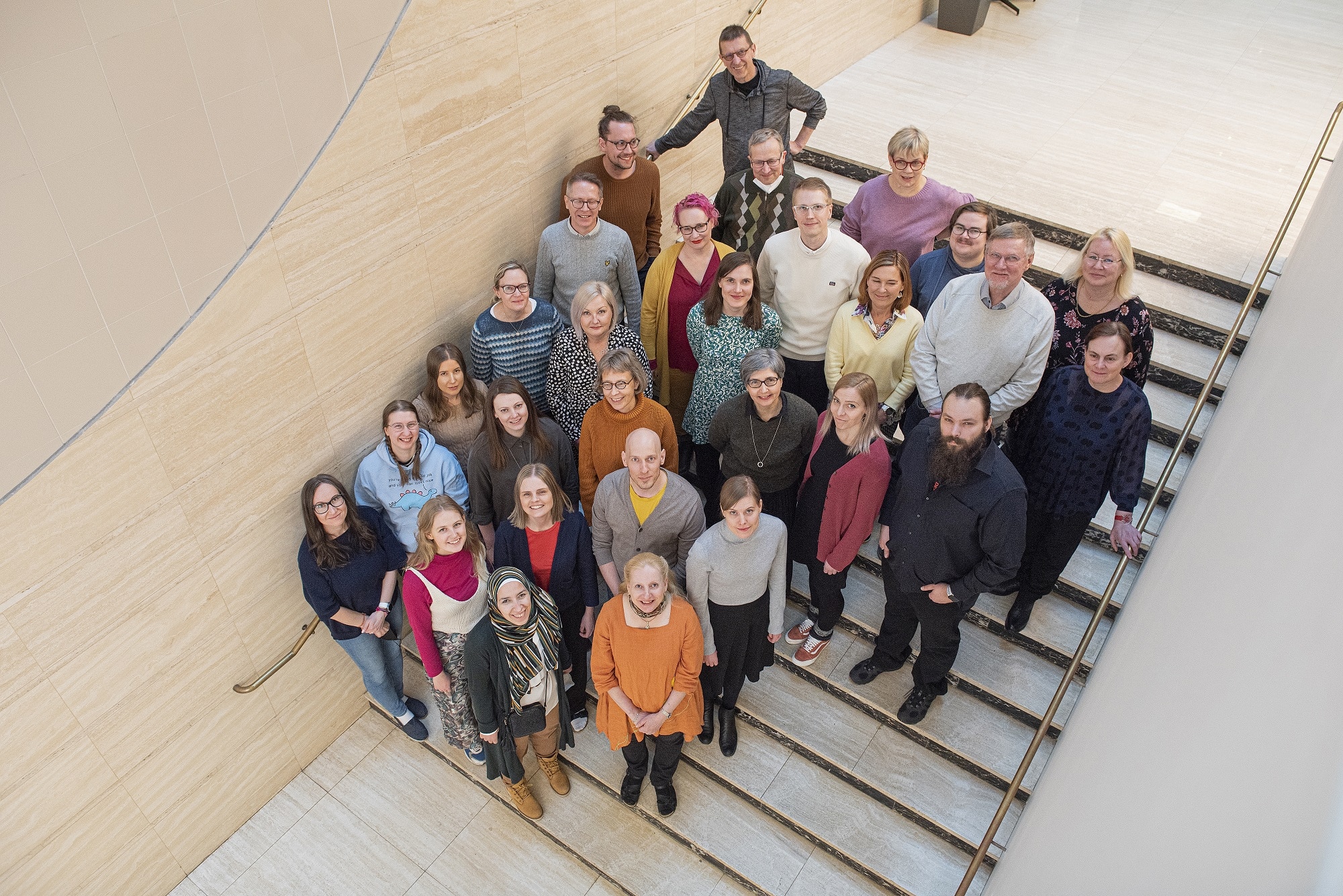

Information, support and hope

One in three Finns will develop cancer at some point in their lives. We want to ensure a good life for every Finn, without cancer and despite cancer. Find out more about our work!

The cancer Society of Finland4500

volunteers participating in our work.

100 000

members of regional cancer associations and national patient organisations.

7,5 million euros

awarded in grants for cancer research a year.

In need of support?

You get personal and expert support quickly and with a low threshold. You can get an appointment the same or the next day. Our services are free and open to everyone.

→Get involved

Thousands of people throughout Finland do voluntary work for the Cancer Society of Finland. Our volunteers are our vital asset. You can take part in the work of the CSF by joining a member association, making a donation or volunteering your time. We value all help.

→

Pink Ribbon campaign

Pink Ribbon is the largest campaign to beat cancer in Finland. Donations for Pink Ribbon campaign support Finnish cancer research and counselling services for cancer patients and their loved ones.

News

Grants

The Cancer Foundation is the largest private funder of cancer research in Finland. It annually disburses over €5 million for cancer research, mostly direct research projects. The Cancer Foundation’s assistance is mainly for conducting long-term research and for well-established teams of researchers. The Cancer Foundation also provides support for completing doctoral dissertations.